“From caverns deep underground to sky-high mountains, the rocks and stones all around us are ancient.”

Folk Tales of Rock and Stone is the new book from Devon author and Jurassic Coast Trust ambassador Jenny Moon. A storyteller with a passion for rocks, Moon’s collection of short stories weaves together history and imagination, drawing attention to a subject that most of us take for granted. From the practical to the magical, Moon demonstrates the integral part that rock and stones play in the transitory lives of humans.

“I have always been interested in fossils and stone,” says Moon, who as a child went fossil-hunting in Purbeck and explored the Fossil Forest at Lulworth. More recently she has taken part in archaeological excavations, notably at the East Devon Pebblebed Heaths.

For Moon, rock and stone are endlessly fascinating. “When you pick up a stone you think, where has it been? Where does it come from and how is it formed? That’s just amazing. Not only, from here onwards, where does it go in the future, long after humans live on the earth, where will this stone be? Will it be atoms again, or will it still be formed?”

Whilst Moon’s book contains folk tales from around the world, the Jurassic Coast and the Jurassic Coast Trust have been sources of inspiration and knowledge. For the section Biographies of Rock and Stone, Moon consulted fellow JCT ambassador Anthony Cline as well as the book Fossils of the Jurassic Coast by JCT’s Head of Heritage and Conservation Sam Scriven. One tale in particular, Jack Tries Smuggling, was written for and performed by Jenny at an ambassador’s event; it details the lives of smugglers and excise men in the 18th and 19th centuries.

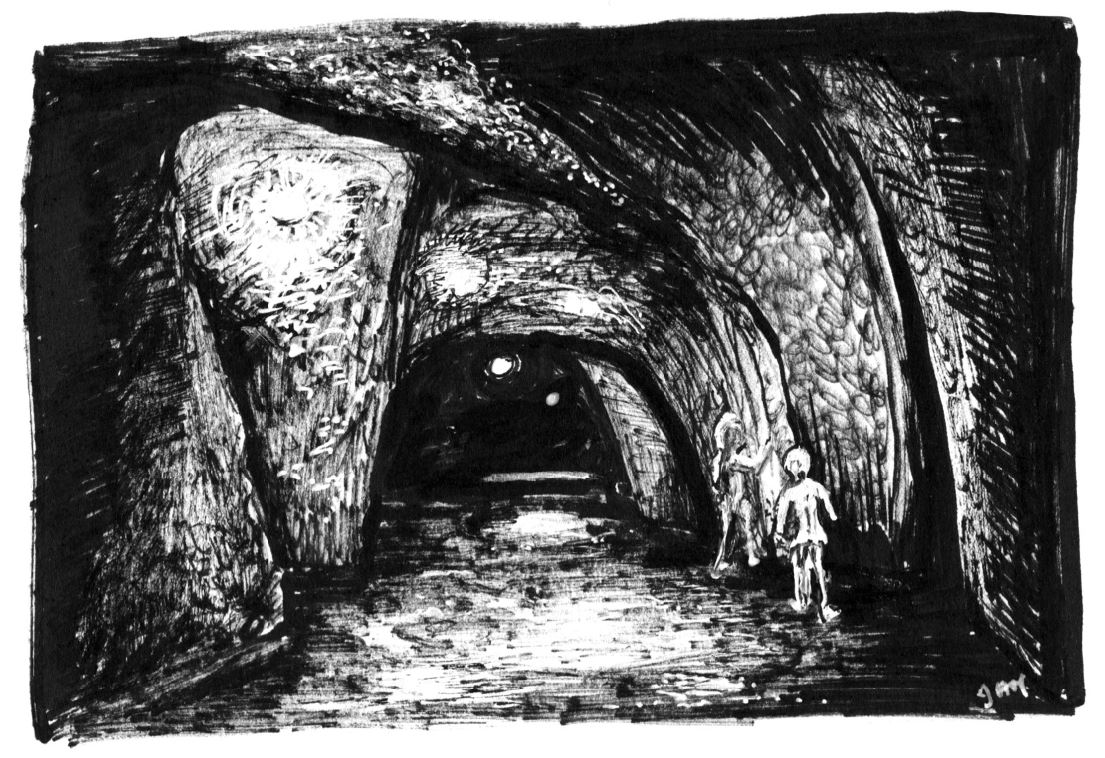

Another tells the real-life history of Beer Quarry Caves – from the harsh conditions for quarrymen to ghosts that linger to this day. Moon describes the caves as “a wonderful inspiration” and muses on their legacy. “I find it stunning that people, the Romans, Normans and Saxons for example, carved the entrances to the quarries according to the architecture of their time… And the limestone has had a life of its own in buildings, such as St Paul’s and also Exeter Cathedral.”

Folk tales too have a legacy of their own. Traditionally passed down orally through the generations since ancient times, they are continuously adapted along the way. Like rocks and stones, they have travelled far: some stories are universal, for example The Stone Cutter and Stone Soup in Folk Tales, whilst Cinderella comes from Asia. “It’s been moderately modified and made into the culture that it’s being told in,” says Moon. “Many folk tales are in fact Victorian in origin,“ she continues, “because that was a time when children’s literature was taking off.”

Since graduating in zoology Moon has had various careers within the fields of health, education and psychology. She is particularly interested in how people learn and the role that stories play, and is the author of several academic books. Her book on reflective learning led to her running workshops around the world; it also gave her the confidence to take up oral storytelling 15 years ago. “I went to hear a storyteller and thought, ‘I can do that.’”

For Moon, attending a storytelling event is a very different experience to say, listening to an audio book. “As a storyteller you have to engage with people, you have to hold their attention… it’s more alive.” The story emerges through movement. “I enact the story,” she says, “to different degrees on different days to different audiences.” She will kneel on the floor when telling to small children to maintain eye contact. Often she’ll hand around a stone during the performance.

Naturally Moon is a fan of reading aloud. “I think some stories lend themselves better to being read out, if the language is important. Poets tend to read their work because of the precision of the language,” she says. “People are mostly going to read them, however reading them out loud is nice and people have told me that quite often.”

Despite Folk Tales featuring a variety of fantastical creatures, Moon doesn’t necessarily believe in fairies and isn’t a big fan of magic. “You can do anything with magic, so it wrecks the story in a way.” She dislikes the Greek God stories for the same reason. She is however keen on the transporting power of stories. “It’s very much about finding a different world within our world. And there’s a point where you leave it. It’s like going out of a cinema, having been really engaged with a film and you think, ‘Where am I?’”

“Stories contain a great deal of unspoken material.”

Moon cites “the unspoken” as key to engaging people with stories. “Stories contain a great deal of unspoken material – leaving stuff to the imagination of the listener is really important. If you’re talking about oral storytelling, then the opportunity for images is key. Oral storytelling relies on generating imagery and feelings in the listener. Rice Cakes for Dinner (in Folk Tales) has wonderful imagery with the ogres bending down with their great wide mouths drinking the stream.”

Stories, according to Moon, can also lose their power through mis-use; in advertising for example, when a story is assumed from a simple image, or in day-to-day life. “Someone will say, what’s your story then? And they don’t mean tell me a story, they mean give me a quick explanation of why you’ve done something.” When I suggest that as a society we seem to be defined by 3-word slogans, she refers to the digital age. “People don’t want to type too much on their phones. I think we relate a lot of what we do to the technology we use.”

Folk Tales is surprisingly free of morals. If anything, it is an educational experience by which the reader becomes aware of just how central rock and stone is to her life. Moon admits she wasn’t looking for morals. “My main concern was to have rock or stone somehow.” And yet, on the occasion when there is a moral, it is suitably down-to-earth: stay humble and be careful what you wish for. The Stone Cutter is a case in point: a man who wishes to be everything but himself, only to find that being a stone cutter isn’t such a bad life after all.

Traditionally folk tales are quite sexist and whilst Moon doesn’t claim to have had a specific agenda as to the role of women, Moon’s tales highlight forms of inequality. The Skimming Stones for example, features a girl beating boys at their own game (like many a feisty woman in history, she is labelled a witch) whilst The Girl who Learned to Hunt is self-explanatory.

Not only did Moon write or rewrite the stories that feature in Folk Tales, she also provided all the internal illustrations. “I love art,” she professes. “The illustrations are all black and white, using fine pens, brush, Indian ink, felt tip… even some potato prints. I just experimented, and because the story was in my head, there was a sense of the image drawing itself.” With a cover designed by Ele Marr that features scenes from the book, Folk Tales is a beautiful object and Moon is happy with it. “It ended up on the shelves at Foyles early on, partly because it looked good.”

As a child, Moon wanted to be an archaeologist only her mother told her “women don’t become archaeologists.” “It was a very powerful thing for her to say,” says Moon, whose path nonetheless has taken her full circle, to excavating the stories of people long-disappeared from this planet of rock and stone.

We would suggest you visit our shop jurassiccoast.link/shop to pick up a copy of Folk Tales of Rock and Stone (£12.99), however we are currently unable to fulfil orders. At the time of writing the book is in stock at Foyles.

Interview by Penny Jones