A liquid fossil

Oil is formed from organic material, mostly plankton, that rained down into a muddy, stagnant sea floor where, rather than rotting, it became trapped in the sediments. Millions of years later, if the rocks are buried deep enough (typically over 2,000 metres), heat and pressure can ‘cook’ that organic material into oil or gas. Because both are light, they migrate up through the rock layers and may become trapped in a porous layer if there is a cap of impermeable rock above it.

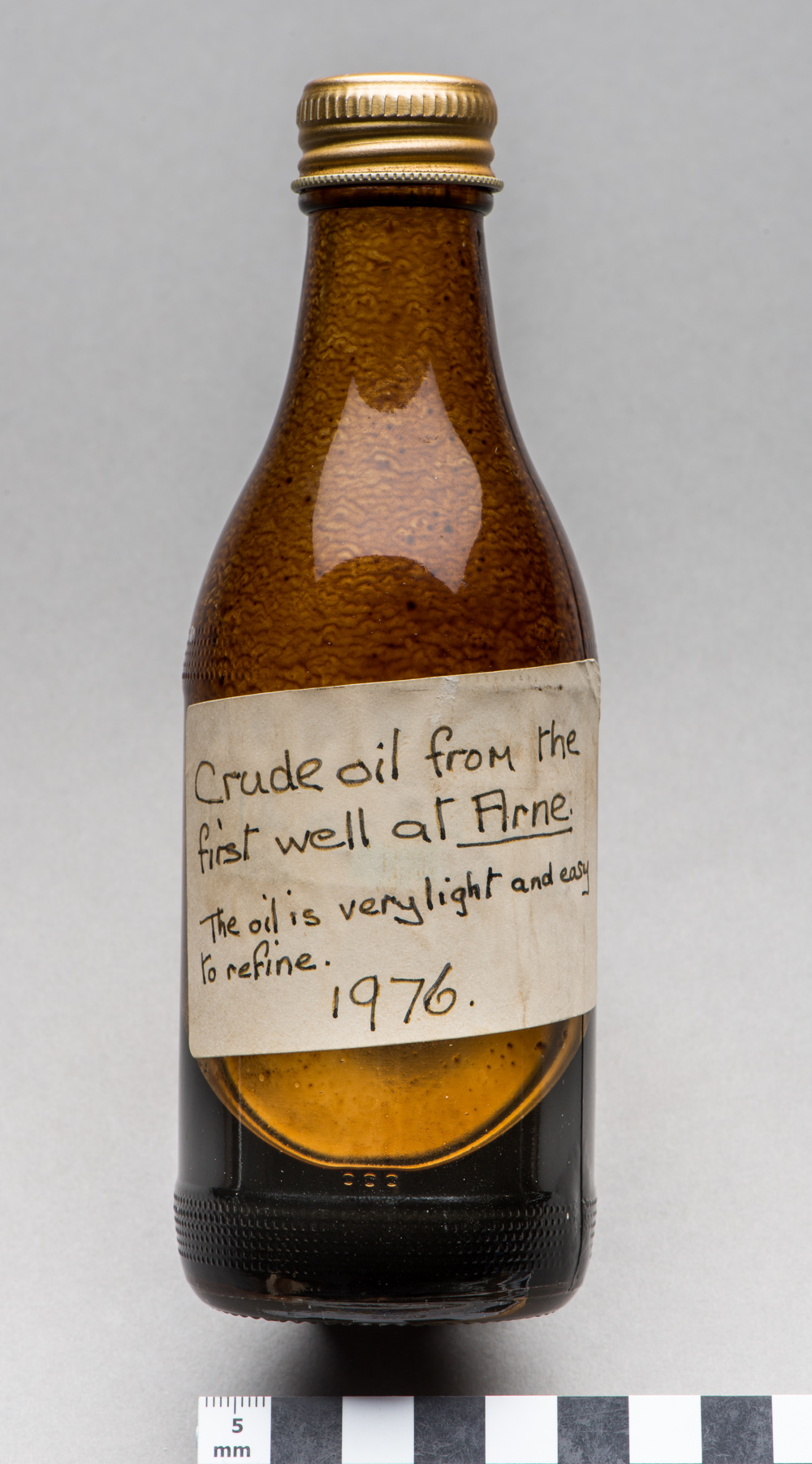

This oil sample from the Wytch Farm oilfield in Poole Harbour originated in Lower Jurassic (Lower Lias) black, organic shale rocks. At Charmouth and Lyme Regis, you can see this rock layer, but it isn’t visible at the other end of the Jurassic Coast. This is because the coast dips to the east, so much so that in Purbeck and Poole Harbour, the rocks are buried underground. In fact, they are deep enough for heat and pressure to ‘cook’ the organic material into oil and gas. The petroleum industry calls these places ‘kitchens’.

The oil and gas has seeped up through the rock layers and become trapped in sandstones: the Bridport Sands and the Otter Sandstone. Both are capped by thick clay, but the Otter Sandstone lies below the Lias so how can that be? The geology is very complicated, so much so that faulting in places has lifted the Otter Sandstone above the Lias. In fact, it took geologists several years to convince the Wytch Farm management that the main oil field was below the source rock. When they finally did drill into the Otter Sandstone, Wytch Farm became the largest onshore oil field in Europe. In its time, it has produced about 400 million barrels of oil. Today the world is consuming about 80 million barrels a day – so a sobering thought is that all of Wytch Farm’s production would power the world for just five days!

Kimmeridge Clay is another major source of oil, but in Dorset it has not been buried deep enough to mature and produce oil and gas. However, in the North Sea it is the main source rock.